Teaching

As Chair in Urdu Language and Culture, I am mandated to teach Urdu language courses, and courses on "the history and literature of the Urdu-speaking people of Pakistan, the Indian sub-continent, and other areas, including Canada" (terms of reference for Chair in Urdu Language and Culture, May 28, 1986). My courses at the Institute of Islamic Studies have followed this mandate quite closely.

I teach the Urdu-Hindi language (both scripts and vocabularies) at all levels, from Introductory to Advanced. Regarding Hindi and Urdu as two varieties of a single language is pedagogically beneficial as well as logically sound. I have been blessed with the aid of capable instructors such as Sabeena Shaikh, Aqsa Ijaz, and Sumaira Nawaz in the maintenance of a full Urdu-Hindi language program. These courses count for South Asian Studies and World Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies programs, as well as the Urdu-Hindi Minor. It is a joyous time indeed when I am able to teach my Urdu Poetry course, ISLA-555, as an alternative to Advanced Urdu-Hindi.

Since coming to McGill, I have also taught ISLA-330 Islamic Mysticism: Sufism. The aspect of Islam known as tasawwuf or Sufism is arguably inseparable from Islam as a whole, so that in fact the Sufism course is an introduction to many aspects of the dīn of Islam itself. With an emphasis on the thought of Ibn ‘Arabi, Rumi, and the Ghazali brothers, my course moves backward from the most difficult concepts (the Essence, Being, the Names) to those that are apparently the most readily understood (Love).

The class that I find most challenging to teach is the class that deals most directly with my own research: ISLA-488 Tales of Wonder. In this course, students read and learn about Islamicate tales in English translation, including the Arabic 1001 Nights (Alf laila wa laila), the Shahnamah or Book of Kings in Persian, and the Urdu Adventures of Amir Hamza (Qissah-i Amir Hamza), as well as others depending upon the year.

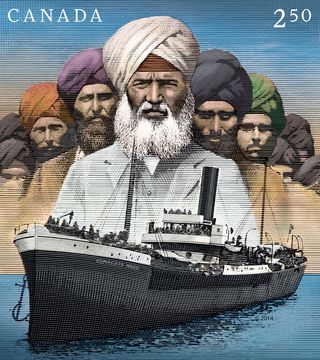

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, I realised a long-cherished project to teach about the Islamicate beyond the so-called Orient, as if Muslims were only a geographically distant object of studies. We are here—and not only us, but many other racialised folks who are conflated with us, or have ties to Muslims, from enslaved West African Muslims, to South Asians in imperial Britain, to Arab Christians and Muslims in early 20th-century Quebec, Sikhs targeted by Islamophobic white supremacism, to queer and trans Muslim communities in Canada in our day. As a diaspora desi Muslim myself, the history and theory of Melancholic Migrants (the latter being taken from Sara Ahmed's chapter of the same name in her book The Promise of Happiness), has been important to me in dreaming a home.